March 2021

Here to Worship the Blue

And then winter left. Ice receded. Snow melted. The grass, mucked with mud, returned.

We got a lot of snow this year. The fall was deep; a trudge, truly, to move through. It seemed like it would never end, but then it does end—and we are reminded that we have been down that route before, that ardent disbelief replaced with surprise.

Now our brook, resurrected by snow, churns and spreads.

We stand in it. We watch hawks bathe in it and raccoons scurry in it.

A bear broke its winter torpor to visit for a drink.

Really, nobody and nothing can stand this isolation for much longer.

We are all waiting for something, yes? The end of this year—not bound by calendars, but by suffering: this collective, heavy grief. It will end. It must end. It will end.

*

"Now that I am old, all I want to do is try; / But when I was young, if it wasn't easy I let it lie."

I can’t stop reading Ruth Stone. I don’t want to stop, really. There will be time for other poets. But it’s Ruth Stone’s time, now.

I’ve enjoyed her work over the years, so this isn’t a discovery—it’s a return, and a strong one. I tend to fall into poets this way: I want to read every word that they wrote, to marvel at them and try to understand their genius.

What draws me to Stone is her resolute desire to exist. “What is this impatience / the widow says every morning,” she wonders. “Who’s here?”

Her husband left this world in 1959, when she was 44, with her first book on the way, and with three children.

The widow, she writes, “brews the coffee / looks through the cupboards. / Today she won’t try to be clever.”

Stone could be so precise with grief—an emotion that often feels amorphous, clouding.

She could be equally adept with her doubt: “I am not one / who God can hope to save by dying twice.”

I often find wonder within unbelief. I am drawn to writers who see the world in different outlines when it comes to God.

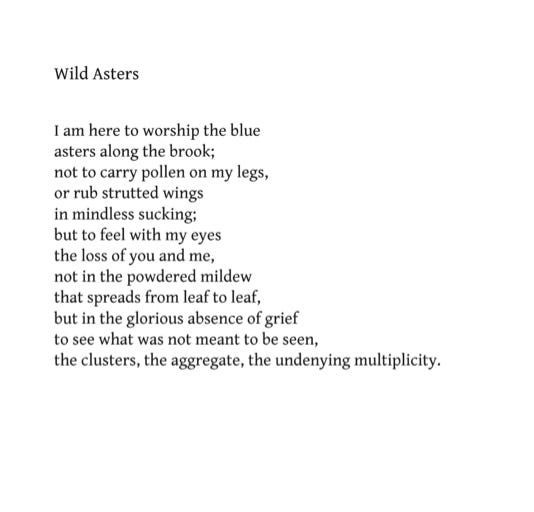

“Wild Asters,” a poem from the Essential Ruth Stone, is steeped in Stone’s affirmation of living. It is a single sentence—which itself is wondrous—and leans into the growth of the longest, final line.

“I am here to worship the blue,” she begins, which compels us to look up to the sky, but then to remember her clever dissociation of the title—we have gone from wild to blue so quickly. And asters are wild and willful in their climbing over each other. They ride the shore of the brook.

She is there for a purpose. She will not be distracted. (Do you hear her in these lines? She inhabits her poems). As so often, the center of this poem is the longing: “to feel with my eyes / the loss of you and me.” And yet, among that infinite blue, she ponders the “glorious absence of grief.”

When do we see what was not meant to be seen? When we drift, when we follow the routes of brooks rather than the trails that cross those brooks.

Imagine this narrator, heart tired, among those impossibly blue flowers, and feel with her “the clusters, the aggregate, the undenying multiplicity.” The world blooms out from her, as if to suggest: how impossible it is to exist, and yet here we are.

Take care—